Moreover, half of the countries do not track the implementation rate at all.

The average implementation rate of planned activities of 55% means that almost a half of the planned activities were not yet carried out. However, such comprehensive action plans and monitoring reports based on reliable sources and pre-established indicators are often missing.

Our analysis shows that high-quality strategies correlate with the existence of comprehensive action plans and ex-ante analysis of corruption risks.

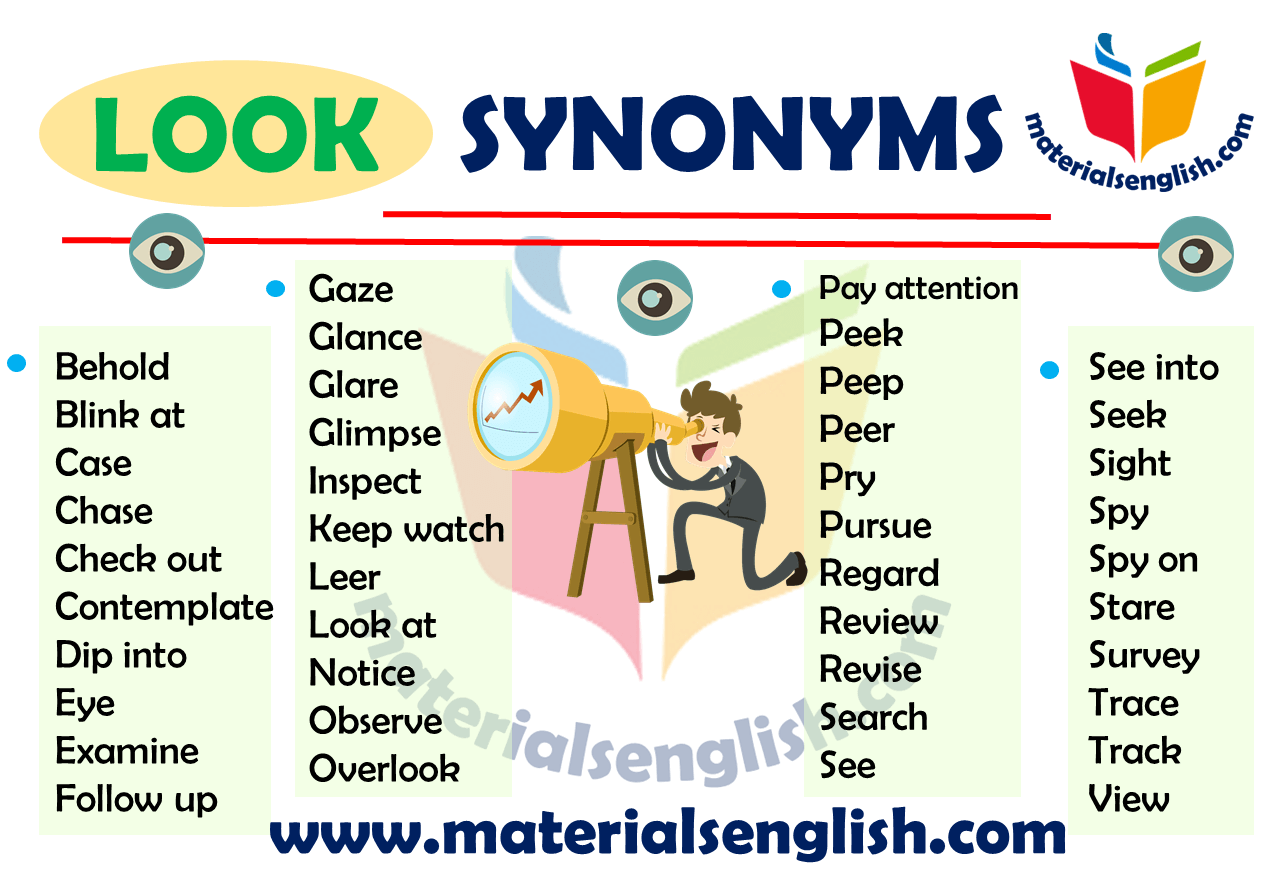

In countries that do set strategic objectives to curb corruption, implementation is surprisingly weak. In many countries, high-level strategic objectives addressing such forms of corruption are missing. One of the central ambitions of the OECD Council Recommendation on Public Integrity – a whole-of-society approach to curbing the most serious and detrimental forms of corruption such as undue influence, political and grand corruption – has not yet been translated into concrete policy objectives. The dataset covers 32 OECD countries and four non-OECD countries 2and shows that: Source: OECD, Public Integrity Indicators. Structure of Strategic Framework for Public Integrity indicator The first data set measures the quality of the strategies for public integrity and anti-corruption (Figure 1) and is described in detail in our recently published working paper Anti-corruption and public integrity strategies – Insights from new OECD indicators ( Smidova, Z., A. 1 The OECD Public Integrity Indicators were developed to monitor progress made in the implementation of the Council Recommendation. The experience of OECD countries shows that addressing corruption requires a comprehensive policy approach, which in 2017 led to the adoption of the Council Recommendation on Public Integrity. Analysts, national administration and international organisations can now explore these data that adhere to OECD standards for statistical quality. It brings interesting insights on how countries are prioritising efforts to address corruption and documents the need to focus more on implementation. The first data set for 36 countries – on quality of the anti-corruption strategy or strategic framework – has already proven useful for decision makers in strengthening their policy frameworks. The indicators unpack the general notion of corruption into specific integrity risks and measure the strength of regulations, institutions and practices. OECD’s new Public Integrity Indicators offer a credible alternative to existing corruption-related indices, drawing directly on data from member countries instead of expert views. The adjective form of focus is focal.By Zuzana Smidova, Agnès Cavaciuti, OECD Economics Department, and Jesper Johnsøn, OECD Public Governance Directorate These senses of focus had spread by the early 1800s, around when various verb forms of focus take off. Focus also refers to ability to concentrate, as in The teacher felt the students struggled with their focus. Optics has also given us the expressions in focus and out of focus, which can be used both literally and figuratively.įrom these various ideas of clarity and convergence in optics arises one of the more common, everyday ways we use the word focus today: “a central point, as a of attention, activity, or activity.” For example, Finding a cure for cancer was the focus of his long career. The word focus took on a number of senses in optics, specifically “the point on a lens on which rays converge or from which they deviate.” A more familiar sense of focus is “the clear and sharply defined condition of an image,” as when the image isn’t blurry. In physics, a focus is “a point at which rays of light, heat, or other radiation meet after being refracted or reflected.” Perhaps you can imagine how a fireplace or a hearth-contained areas and sources of heat and light-was likened to such a point in math and science. Other applications of the word focus in the late 1600s came about in the fields of medicine and physics.

So did Isaac Newton-you know, of gravity fame-in the 1690s. In the 1650s, the influential English philosopher and author Thomas Hobbes used focus for a kind of fixed point in geometry. As the 1600s unfolded, focus was given new meanings in the great scientific literature of that age, which were largely written in what’s known as New Latin. This is what focus originally meant in English when the word entered the language around 1635–45, though that sense has been extinguished, as it were.īut the word focus burned on in other ways. Well, the word focus comes directly from the Latin focus, which meant “fireplace” or “hearth” (that is, the floor of a fireplace). Or perhaps you recall a teacher tsk-tsking you to pay attention in class. What does the word focus bring to your mind? Maybe you think of a photograph that is clear and sharply defined.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)